Value Economics

free market solution to all social & economic ills

|

|

|

Search this Page: Press Ctrl+f to find any term or phrase on this page (Cmd+f for Mac). Search this Page: Press Ctrl+f to find any term or phrase on this page (Cmd+f for Mac).

|

|

| Author |

Message |

|

|

| Value Economics Posted: September 3, 2009 |

|

|

NOTE:

A separate website has been set up to educate the public about Value Economics β

visit: FreeAmerica.us (under construction)

Value Economics

A True Free Market for True Global Freedom

Summary Points: - Accounts for full value β including ruinously costly economic externalities (side effects) β to achieve true pricing, profit incentive, and production value; solves problems of health, education, social welfare, infrastructure, security, energy, resources, and environment, including climate change.

- Improves business and economic efficiency through perfect competition & information.

- Self-regulating to function smoothly and robustly without government or central bank intervention, and without debilitating boom/bust cycles.

- Self-enforcing to safeguard free market functioning without constricting regulation and bureaucratic control; every citizen protects the market.

- Creates free market mechanism to protect, preserve & promote the value of public goods; ends 'tragedy of commons'.

- Distributes wealth and dispenses social justice fairly through free market exchange, according to merit, free of class bias, and without social engineering.

- Minimizes (or eliminates) taxes and maximizes investment; ensures capital flow to highest value outcome, including public needs: citizens invest in the nation.

~ ~ ~

Free market economics is a crown jewel yet to be set on the true throne of freedom.

Economic freedom β as we know it β has proven to be a mixed blessing for society. Our free market system has brought great prosperity and progress, but all too often it has the opposite effect, creating problems that drain our resources, sap wealth, leave waste, divide society, and erode our quality of life. Vital needs go unmet, quality of goods and services fail, and negative side-effects eat up value. On rare occasions, our economy spirals into meltdowns that threaten the very fabric of the free market system itself. They force us to compromise market ideals in order to save the system. Bailouts, regulation, and other intervention water down the value of economic freedom. Booms have been our blessing, but busts our curse.

Fortunately, the curse is a mixed blessing too. Economic suffering aside, downturns present both a challenge and opportunity. The challenge is to examine our economy and see why it doesn't always produce the result we want. Is there merely a bug in the system or is the system itself to blame? If we accept this challenge and probe deeply, we find that the ideal of economic freedom is sound, but that the flaws in our version of it are far more fundamental than we think. Free markets work, but we don't have a true free market. This presents the opportunity.

The opportunity is to re-explore and restore true free market ideals. If we embrace this opportunity, we will not only solve our economic problems, but also transform free market economics into a system that solves all of society's ills. We will create a market economy that accounts for all that is best in humanity, and manufactures that into economic output. We will forge an economy that employs all of our hopes and dreams β our best values β and crafts them into goods and services. We will construct markets that assemble every resource of human potential and fashion from that our material world. We will discover that free market economics is a system so perfect that it can bring forth β literally β a utopian society.

Through a pure freedom ideal we will remake economy, and in so doing, remake our world.

Freedom is our heritage. It opens the door to the blossoming of the human spirit. Economic freedom β in its pure form and true expression β monetizes and materializes that spirit. It manifests the full value of that spirit. Economic freedom makes the human ideal practical.

Free market economics thrives on the opportunity to meet society's needs. It flourishes on the chance to satisfy human desire. A true free market economy meets every human need and satisfies all desire. It succeeds because at the same time, it cultures holistic life built on honest need and balanced desire. It fosters life in harmony with the resources that nurture and sustain it.

A true free market works the same way our broken one does, without the failings. If that sounds modest, it is only because the failings are so chronic and ingrained that we no longer even notice, accepting them as part of the system. The system is so broken that we don't realize the extent of the break.

An added woe of economic crises is that, while they motivate us to reform the system, they mask the broader problem and therefore blind us to more fundamental solutions. We see only the immediate financial crisis, and not the more systemic sickness. We fail to comprehend the true nature, depth, and scope of our economic plight.

We also miss these issues because we're caught up in the areas they impact, ignoring the underlying economics. We face a health crisis, an education crisis, social crises, environmental crises, and an energy crisis. We see all these as distinct and separate from economy, but they are not. In every case, the underlying economics fail to fuel solutions to these problems.

We don't so much face a health crisis as we do a health economics crisis. Our environmental crisis is fundamentally an environmental economics crisis. Our education and social crises are also rooted in economics, as is our energy crisis. Even our international crises have major economic components.

The root problem is deeper even than this. We do not even face a collection of economic-related crises in these fields. Fundamentally, we face one crisis alone, a purely economic crisis. In every case β health, education, society, energy, and environment β the profit incentive that drives our free market system fails to spur solutions to the problems at hand. Yet for each crisis, solutions either exist or can be developed given financial incentive. With proper incentive, the free market will solve these crises the same way it meets every need: through innovation, applied resources, skilled training, and work.

This crisis is not new. Our health, social, and environmental problems have not suddenly exploded onto the scene. Rather, they have been brewing and growing β sometimes in view, sometimes not β for years. They are chronic burdens present long before any current meltdown, and will weigh on us long after if we don't treat the real crisis.

Nor is this economic crisis based in political ideology. It is not a matter of government involvement, regulation, or taxation. Again, it is purely economic. If the free market works as it should, questions of ideology become moot. Ideology rages because the system doesn't work. So we fight over whether and how government should fix it.

While the depth and scope of the problem may sound dire, it is actually good news. It means that, because all these crises stem from one basic problem, they are resolved by one fundamental solution. A working free market system solves them all. We need only restore true free market principles.

A true free market is self-regulating, self-correcting, and a self-dispenser of economic justice. It self-manages economic and environmental resources, and self-promotes personal and social welfare. A true free market centers on the emblem of economy: value.

Value is the measure by which we assign a monetary number to everything we buy & sell. By accounting for all value we can measure, we set fair prices in the marketplace, and let economic freedom do the rest. This translates to maximum value in economic output.

The economic system that achieves this is a free market economy, but being an evolution of our current system β which ignores value in many ways β it is best termed 'Value Economics'. The name reminds us of its aim. Value Economics maximizes production value. It is a free market system that runs smoothly, free of intervention. Value Economics restores full value to the ideal of economic freedom.

Economics today is at a crossroads. We face a crisis far deeper, broader, more systemic, and costlier than any current financial crunch. The up-side is that with one deep, broad, systemic stroke, we can solve not only our economic crisis, but also our many other crises, and achieve our full economic potential. We do it simply by making our free market work as it was originally intended to work.

The direction we choose at this juncture in time determines our economic future for generations. We can address this crisis in cursory fashion and wait for the next to occur, throwing good money after bad while fleeced by our own economy. We can invest β poorly β in patchwork solutions, waiting for the next bubble to burst. Or we can see the enormous economic value β and human value β in doing it right, and make a sound investment in restoring the system. That is the wiser economic choice.

When systems fail, we question our core values. In times of economic crisis, we debate our free market ideal. Some say leave it alone and accept its shortcomings and occasional crashes. Others say intervene to control and shore it up. Still others β opponents of the free market system β say abandon it all together.

Should we forsake free market economics? No, we should perfect it.

Free market economics is not ready for rejection. It is ripe for revolution.

The ideal of economic freedom burns as brightly today as ever. To restore its full value, we need only return to the root of its glory.

Free market economics was a revolution in itself and is steeped in revolution history. It arose amidst a sea of economic turmoil. It is credited with fueling the industrial revolution, which brought great progress and filled society with a spirit of achievement. Today, rising from our own economic turmoil, we can spark a new economic revolution β not an overthrow of our past, but a renewal of it β and rekindle our entrepreneurial spirit once more.

If we do, we will inspire an age of innovation and abundance, founded on holistic values, the likes of which we have never seen. Economic freedom will literally set the world free.

To understand that this is no exaggeration, let's explore the promise that economics holds.

It lies in the spirit of that word which is everyone's favorite economic term: FREE.

DAWN OF ECONOMIC FREEDOM By all historical accounts, 1776 was a banner year for freedom. Most know 1776 as the year of American Independence. On July 4 of that annum, colonial leaders signed the Declaration of Independence, beginning a new age of political freedom.

Political freedom is no doubt a blessing to civilization. It unleashes the creative genius of man & woman for the betterment of all society. As a governing principle, it protects our sovereign birthright as free human beings.

Remarkably though, it may be that the declaration of political freedom in 1776, for all its impact and worth, was not even the most vital freedom established that year. That exalted honor may instead go to a declaration of economic freedom β published the very same year, 1776 β by a largely unknown Scotsman named Adam Smith.

Smith's book, titled The Wealth of Nations β well known to economists, but few others β set down the principles of free market economics. In doing so, it lay the foundation for economic freedom in the world.

While economists avidly affirm the seminal nature of Smith's work, not even they likely would go as far to suggest that it surpasses the famous political declaration of that year. But despite the lack of annual fireworks to back it up, we can make a serious case for it.

For while a nation's political system no doubt sustains the life of its people, on a daily basis its economic system impacts them more.

How often, for example, do you exercise your free speech right to protest government, or demand action on a strongly held view? How often do you believe government β 'representative' as it is β actually does your bidding? How often do you neglect to vote because "it doesn't change anything anyway"?

In contrast, how many times a day do you buy something you want at a fair price, to provide for your wants and needs? How many times do you marvel at the mall at the incredible variety of products available? Phrases like, "what'll they think of next" and, "too much to choose from" come to mind.

When was the last time government came out with a technological innovation β like the automobile, television, or computer β that transformed life overnight?

There is no doubt that political freedom has a silent value that we take for granted every day, but economic freedom is more responsible for advancing our quality of life. We might say that political freedom's best feature is providing the environment for economic freedom to flourish. Indeed, the two invariably go together in society, making their tandem 1776 declarations all the more extraordinary.

But economics is a ruler of life in its own right. How often are your shopping, activity, entertainment, or other plans dictated by the economics of price and availability? We drive the extra mile for that sale, or because one store has exactly what we want. We go here, not there, because of brand or because it's cheaper. We change plans because they're out of tickets or out of stock.

Not just little things, but major decisions too. We take that job because it pays better. We send kids to college within our budget. We put off that car to pay for the wedding, spending it on a thousand dollar dress. We retire when our end-of-life savings are secure. All these choices are economic.

Economics governs our lives. It is the prime mover of behavior on a day-to-day basis. The daily act of earning a living and providing for self and family directs societal life.

Politics itself bows down to economics. "It's the economy, stupid," is ingrained in our political lexicon. Elections are won & lost on the issue. Thomas Jefferson, one of America's great political leaders, paid it homage: "I place economy among the first and most important virtues...."

One notorious sign of the sway economy holds over us is that old adage, "money is the root of all evil." While this seems to undercut the vision of economics as savior, it hints the reverse. If we can use money in a truly positive way, it can be a means for all good. Our economic system holds that much power.

Remarkably, Adam Smith's free market ideal holds the key to do it, if only we apply it fully. All we need do is restore full value to money, and what it buys.

ECONOMIC VALUE Economics is, if nothing else, the science of value. It quantifies value and manages its exchange to produce output of value for society.

Value itself is abstract. The challenge of economics is to quantify and account for it as accurately as possible. Economy fails to produce ideal output when it inadequately accounts for value. Such is the case with economy today. For all its achievements, we can do better.

To see how, let's get a grasp on this abstract thing called 'value'.

The first, and most important, thing to know about value is that you decide it. In a free market, you β not government, not elite economists β determine the value of things. This is the first hint of the transformative power of economy. There is no bureaucracy, no planned management, no political agendas, or ill-conceived ideas. There is just you and your wallet or pocketbook to decide value.

So what is value?

Typically, value boils down to the simple notion of how much something is worth. This is so basic to free market exchange that we take it for granted. Every time we shop, we consciously or unconsciously decide how much products are worth. But even this most basic concept has more impact than you think.

To demonstrate, let's discuss the value of things, starting with one that is part of every economic exchange: the money with which you buy.

Value of Money Believe it or not, you decide the value of money. That's right. Money only has value to the extent that we give it.

This is more than hyperbole or semantics. Paper money, unbacked by a commodity valued in its own right (such as gold), is worth only the value we give it.

Unbacked currency is technically known as 'fiat' money. Fiat simply means "by authorized decree". In other words, the money has value because government says so. But that is only half the story.

Government decrees that the national currency (in America, the dollar) has value, but it does not decree how much value. That depends on economic factors.

One such factor (a major one) is money supply. When a nation's Central Bank (in America, the Federal Reserve) authorizes the printing of more paper money, its value goes down because there is more of it. More money serving the same economy means less value for each currency unit (i.e. dollar). An example makes it clear:

If there are $100 in circulation and 100 loaves of bread comprising the entire economy, each loaf might sell for $1. If the money supply suddenly grows to $200, each loaf now costs $2, because there's more money buying the same bread. Each dollar then, is worth only half of what it was: $1 buys half a loaf. The value of $1 is now 50 cents. There is a common term for this: inflation. If you want a real world lesson, ask your parents what a dollar bought when they were young.

Inflation is stark truth that the value of money is its real worth, not some dollar designation.

Money supply though, merely influences its value. It doesn't set it. That power remains with you. If, in the market, you and everyone else refuse to buy bread at $2 per loaf, the price comes back down. If you are steadfast, you can bring it back to $1. If you're irate at the price hike and want to teach the baker a lesson, you and your fellow shoppers can boycott the bakery, driving the price down more.

This is the most well known principle of economics in action: supply & demand. When demand drops, so does the price. You, the consumer, controlling demand, ultimately set the price. And thereby, you set the value of your dollar.

Every time you buy or don't buy an item, you change β ever-so-slightly β the value of money. If you buy, you tell the market that the item is worth more than your money. That devalues the dollar, literally. (By buying, you increase demand, driving up prices. With higher prices, your dollar buys less: it is devalued.) By not buying, you say that your dollar is worth more than the item. By holding onto your purchasing power, you increase the value of the dollar.

These value shifts, of course, are microscopic. They're the domain of microeconomics, which studies individual transactions in the marketplace. But don't be fooled; how you value things can have macroscopic effects. To see the dizzying β and devastating β power you have, just look at the times when we all act as one. Then we, the people, have far more power to set value than any Central Bank. We can make things exceedingly over-valued...or practically worthless.

Before we give some examples, note that value is always relative. When you shop, you're not so much setting the value of money or products as you are weighing the relative value between them. With each purchase decision, you ask, "Which has more value to me, my money or the item?" If it's the item, you buy; if it's your money, you keep it. That's why in every exchange (or non-exchange), the value of one goes up while the other goes down.

So the following extremes, which we typically see as over- and undervalued assets ('items'), are just as truly over- and undervalued money. They should be painfully familiar:- Wall Street Crash of 1929;

- Black Monday, 1987 (largest 1-day % stock decline in U.S. history);

- Dot-com bubble...and burst, 1995-2002;

- Housing bubble of the 1990's...and burst, leading to the subprime mortgage meltdown and global financial crisis of 2008.

In each case, consumers (typically investors) bought something in great quantity, driving prices exceedingly high. Values skyrocketed above their true market value. When unsustainable levels peak, they plummet. Economic disaster results.

The Dot-com crash at the turn of the millennium by no means had the greatest impact, but it's an excellent teaching tool for several reasons. The main one is that it weighs the value of something highly intangible, like fiat money itself. The Dot-com boom & bust centered around the value of stocks (paper certificates of value) of startup companies (with few hard assets and no track record) competing in the internet market (unproven, existing only in cyberspace, and lacking traditional market territories) against virtually identical companies (same business plan and model, with only a different dot-com name).

Nearly all value was in everyone's head. With very little real and concrete worth, the Dot-com boom/bust shows how our perception of value has huge economic impact.

The Dot-com event also teaches well because it clearly shows both sides of the story.

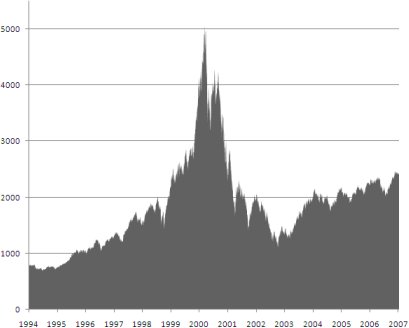

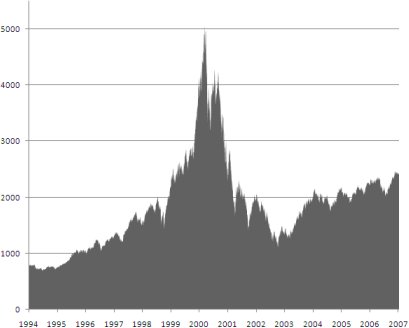

There are two phases to every boom/bust cycle. Both misgauge true market value. The Dot-com bubble (boom phase), from 1995-2001, saw the NASDAQ stock index (serving the tech market, including internet cos.) rose from under 1000 to over 5000 in March, 2000. Most of that was in a frenzied 1 1/2 year period that saw the index more than triple in value. Hi-tech wizards quit traditional jobs, competing in cyberspace. They were all looking to cash in on perceived value.

At the very outset of the bubble in 1996, Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan made an oft-quoted remark, warning of "irrational exuberance" in the stock market. Translate that as overrated value.

The Dot-com bust was equally dramatic, wiping out $5 trillion in market value from March, 2000 to October, 2002. Most of that came in one short year. As of 2008, the market is still barely half of its peak value.

How real is the impact of perceived value? If everyone today were to suddenly decide that the stocks again had value, tomorrow they'd be back at 5000. The likelihood of that happening may not be real, but the economic impact of how we gauge value is very real. It almost defies logic, but it is.

The NASDAQ chart below clearly shows both the rise and fall of tech stock value:

Another reason we can well learn from the Dot-com episode is the balanced nature of the cycle. The near perfect symmetry of the Dot-com swing might even be beautiful, if the downside weren't so painful. But that's the point. We lament the $5 trillion lost, but if we overvalued it to begin with, was it ever really there?

Balanced between every boom & bust is true market value; everything else is, well, misvalued.

All this results from how we quantify, measure, and account for value. And when we set the value of items in the market, we also set it for the money with which we buy. Booms & busts exceedingly inflate, or deflate, the value of money.

It may be mind-boggling to conceive, but the same statement made earlier about stock value can be applied to money. If everyone today agreed that our money was worthless, it would be so. Don't believe it? Look it up:

The Random House Unabridged Dictionary (2008) defines 'fiduciary' thus: "depending on public confidence for value or currency, as fiat money." Money, like everything else, only has the value we give it.

Value is everything. Economy trades in value, not money. Money is just a medium of exchange. What we exchange is value. Economy must represent true & full value.

That is the need for Value Economics.

Economists will argue that our current free market system correctly accounts for quantitative value through the law of supply & demand. It weighs the value of supply (production costs) against demand, the item's value to buyers. As explained above, every microeconomic purchase (and non-purchase) contributes to its consensus value. That sets the "true" market value.

But what about booms & busts, and the more common but less extreme inflationary spurts & recessions? Something more than single market transactions are setting value. 'Irrational exuberance' and equally unreasonable panic & fear distort value and drive it to extremes. Do we account for these in ways that help to smooth the bumps? Value Economics does.

But there are even greater unaccounted for values in the equation. What about health, social, or environmental costs (and cost benefits) associated with goods & services? These are very real β and vital to society β yet rarely included in product value. Shockingly, this is the sole reason economy doesn't produce what we want in these areas. Value Economics does.

Before we explain how, let's explore another side of value.

Value Quality Above, we talked about quantitative value: that money (and what we buy with it) are worth certain amounts or they're not. That is certainly important, and Value Economics increases economic efficiency and improves its functioning, producing more output. It also stabilizes the economy so that it has fewer and shallower recessionary swings, where monetary value is lost. But this is not its main contribution. Quantitatively, our current economy does pretty well. There is definitely room for improvement β and devastating value meltdowns must be eliminated β but overall, production and growth are good.

That in itself is a testament to free market principles, and hints at the productive potential we can unleash by applying those principles truly and fully. As you'll soon learn, there is much in our current economy that inhibits free market functioning.

Beyond this though, is something more than quantitative value. That is qualitative value. This is the real contribution of Value Economics.

We're not talking here about the quality of our cars, clothes, and appliances, etc. Again, our current economy does a decent job at that. Rather, we're speaking of overall quality measured by a broad spectrum of human values.

To show exactly what we mean by value quality, and how vital it is to a related value β quality of life β let's examine the economy of a small, hypothetical nation. It also clearly shows the difference between qualitative and quantitative value.

A Tale of Two Economies

~ Part I ~ We'll call this country, 'Dollarland'. Its population is two, which conveniently simplifies our study of free-market exchange. Dollarland's economy is vibrant. Here are the statistics:- 100% employment;

- 0% inflation;

- $100,000 per capita gross economic product;

- $100,000 per capita income;

- 100% annual economic growth;

- 100% equal distribution of wealth.

Based on quantitative value, is this a healthy economy? Any economist would say, 'yes'.

Let's look closer.

Dollarland's economy is famous around the world. Some would say 'infamous'.

One of Dollarland's citizens produces and sells guns; the other traffics in drugs. Together they make a dynamic economic duo, transacting with each other, annually doubling their production, sales, and wealth, to the tune of $100,000 each in the current year.

Dollarland's vigorous economy thrives another day, until one accuses the other of theft. A fight ensues, and they each pull a gun and shoot the other dead. Immediately after, two citizens return to the country from overseas, looking for work. Finding only guns and drugs, they gather the items and pick up exactly where the first two left off, leading to their own fatal duel. Fresh citizens fill in again, doubling their wealth until death. Thus Dollarland's economic cycle repeats, producing ever-expanding growth.

Now, based on complete value, is this a healthy economy?

The value difference is quality.

If you need figures to drive home that this also has real quantitative value, here they are:- 100% drug use;

- 150% crime rate (2 murders, 1 theft);

- 100% mortality rate;

- 0 housing;

- 0 healthcare;

- 0 education.

Of course, in a real society impacting others, these would have real dollar costs, including law enforcement, public housing, drug abuse treatment, healthcare (gunshot wounds), and lost production in more useful economic sectors.

While obviously extreme, this example makes graphically clear that there is more to economy than money and quantitative value. Numbers do not tell the whole story. What is missing in Dollarland's economy?

Full Value The answer is what we've been discussing all along: value. Not mere 'utility' value, but broad human value.

Dollarland's goods and services do not represent all that society values. Economy aims at producing value, not mere money exchange. Quality matters as much as quantity; what we produce impacts our quality of life more than how much. Economic abundance ultimately has little value if it doesn't give us the life we want.

This doesn't mean Dollarland's economy has no value; it just lacks full value. Its goods and services provide some immediate value. But why does it not produce a better society?

The reason is that value is not restricted to obvious goods and immediate services, or mere labor and materials. Full value includes these, but also more. It encompasses everything we cherish in life β the full spectrum of human values. Their worth is expressed in their name: values.

We value health, vitality, and longevity in personal life. We value quality education for our children. We value social justice, order, and welfare. We value art & culture. We value appealing urban environments and sustainable resources. We value clean air, water, and land. We value peace.

Value applies to every facet of life. These are real economic commodities that we desire.

If long, healthy life were available in the market for a price, would you buy it? Many, if not most, would. Most would also buy crime-free society and a clean environment. If these are real economic commodities that we would pay good money for, why aren't they included in price insofar as products impact them?

Dollarland's economy, like ours typically does, only accounts for immediate and obvious values. These drive the economy, deciding the goods and services available. They also set relative prices between products, influencing which ones we purchase. Even when full value products are available, price motivates us to buy inferior ones because it doesn't account for their true worth. Thus, our economy promotes immediate value at the expense of greater, overall value.

And because of its power, economy blinds us. We get wrapped up in the money aspect. Dollarland's citizens want the best guns and drugs at the cheapest price, thinking that's the ideal. Chasing dollars, they never have time for their real values. They lament the 100% murder rate, but think, "What can I do about it?"

What kind of society does this create? Like Dollarland's, not the one we want. Consider the following problems we face, and the economic conditions that perpetuate them: countless social ills, which many products & services contribute to, despite the cost; failing education, which we fail to fund with the enormous cost benefit it brings; poor public health, which we perpetuate with products that ignore huge health costs & cost benefits, and fight with a medical system that profits when we're sick; crumbling infrastructure, which we ignore though that cost is more than the cost of rebuilding; energy crisis, which we fail to address despite the vast economic windfall it would bring; environmental pollution, which we never account for until taxpayers must clean it up; underdeveloped arts, while economy promotes 'starving artists'; and billions spent preparing for and waging war, which ignores the enormous economic value of peace.

Worse, because economy doesn't address these issues as it should, we dump them off on government. Then we fund the bureaucratic mess by a method that we seek to minimize: taxes! Thus, we tackle ever-growing problems with a hopefully ever-shrinking pool of money. How economically prudent is that?

If we don't want these things, why does our economy promote them? Economy is to serve society, not enslave it. Its purpose is to produce value. Value is what we desire, not economy replete with negative side effects.

Now think if the opposite were true. What if chasing dollars produced all the things we value? Envision economy solving β no, preventing β these problems, one purchase at a time. Imagine the world we can create by awarding profit to the values we want.

That is the promise of Value Economics.

Value Economics is a practical way to promote better health, education, social welfare (reduced poverty, crime, drug abuse, etc.), environment (sustainability & preservation), and even international relations. Yes, merely by exercising the power of your pocketbook, you can qualitatively improve every area of life, including promoting world peace. That is the promise β and power β of Value Economics.

Value is everything; what we value and how much. Value Economics restores quantitative and qualitative value β full value β to economy.

The above introduction has been lengthy, but it was needed to show just how central and vital value is to the economy. In doing so, it makes clear that by truly and fully accounting for value, we can wholly transform economic output, qualitatively and quantitatively.

Now it's time to learn how to use the power of value. By exercising your power in the market, you help build the society you want.

THE FREE MARKET IDEAL Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, despite limited fanfare, has endured over two centuries of economic thought and is still regarded as an accurate presentation of free market principles.

Smith's basic premise was that individuals, acting in their own economic 'self-interest', serve the needs of society. This oft-cited passage makes the seemingly paradoxical point:

| Quote: |

| "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages." |

It could not be a simpler or more beautiful system. We take care of ourselves, as is natural, and in doing so, we take care of society.

If we accept the free-market ideal (and there have been critics, which we'll discuss later), then we must assume that if economy doesn't promote all we want in society, we haven't applied the ideal truly. That is exactly the case.

Value Economics aims to fully & truly apply the free market ideal.

The mechanism by which the free market operates is profit incentive. By rewarding profit for value, economy motivates individuals to seek and produce value.

What is so powerful about profit incentive is that it can motivate people to just about anything. That can produce positive or negative results.

But if you think about it, it shouldn't be so. Everyone wants positive results, or at least, most of us do. Why then, would we create incentive for negative outcomes by paying for them?

Why would we pay to become sick? Why would we pay for social ills? Or a depleted or polluted environment?

The answer is that we don't. That is, we don't pay for them when we buy things. They come as unintended or ignored side effects.

We don't pay these negative costs in our transactions because we don't account for them. They're not part of our pricing equation, so they don't figure in. We leave out part of the total value.

How we account for value determines whether our economic output is good, bad, or mediocre.

It determines how profit incentive works. If we fail to fully account for value, we create misplaced incentives. We establish incentive for unwanted outcomes. We also miss incentives for positive ones.

Profit incentive (as it now operates) creates much good in our economy, but not all good. It partly fails because it mainly rewards immediate values: what we want and need now. We pay to satisfy immediate desires. Profit incentive currently doesn't adequately reward (or discourage) broader values that range beyond the present transaction. It neglects health, social, and environmental costs that show up later and/or impact the broader society.

In short, profit rewards some negative things and fails to reward many positives. In economic terms, it is 'inefficient'. Value Economics maximizes efficiency by better accounting for what profit does and doesn't reward.

Some may regard this as a luxury, not a necessity. They may agree that economic output would improve, but at added cost. They might suggest that we're better off accepting the negative effects in order to save the cost.

That argument though, is critically flawed in every way.

First, the truth is that we DO pay for negative economic outcomes. We pay in cold, hard cash.

We pay for negative health effects through healthcare costs and lost work production. We pay for social ills through costs of crime & justice, insurance, and social programs. We pay for environmental impact through waste disposal costs, toxic cleanups, more healthcare, and resource hikes. We pay these costs elsewhere in the economy, often through taxes. We pay down the road or we pay a different piper, but we pay.

Since we pay the costs anyway, why not account for them up front and eliminate the problem? By ignoring them, we not only pay the dollar cost, but also we suffer the problem. We pay twice.

Plus, the financial burden is more. It costs a lot more to clean up a mess β whether it's health, crime, or the environment β than to prevent it in the first place. As you'll see later, these costs are enormous. Preventing these ills comes at cost savings, not added cost.

Far from being a luxury, full accounting is an economic necessity. It is our current partial accounting that costs more. These real dollar costs drain the economy. We can't afford them.

We're not done yet. We pay yet a bigger cost.

We pay the untold cost of missed opportunities for innovative solutions by not fully rewarding them in the marketplace. Instead, we discourage solutions because immediate costs may seem higher, though long-term cost is lower.

How many health & energy solutions have we missed because profit incentive is not high enough? How many environmental solutions remain unfound due to lacking profit incentive? These costs are crippling not just to economy, but to our quality of life.

By accounting for costs & cost benefits up front, we encourage solutions through profit incentive. We save both suffering and money. We can use that money to produce other things. We also enjoy the value and benefit of real economic solutions.

Is It Broke...? Some may go even beyond the luxury vs. necessity debate and take a stronger stand. They might argue, "If it ain't broke, don't fix it." But is our economy broken?

We can answer this two ways: in practice and in principle.

In practice, let's look at results. These are clearly mixed. On the one hand, our free market has afforded us great material progress and comfort, and improved our standard of living. On the other, it has delivered inadequate healthcare, contributed to social problems, left a wake of pollution, depleted our resources, and brought profit to war; all with high taxes, huge deficits, and poor distribution of wealth. Did we mention financial meltdowns?

Even our material comfort has its downside. Our economy promotes a wasteful, ad-crazed, fad-obsessed, mass-consumption society, where 'disposable' means value and today's 'new' is tomorrow's trash. Creature comforts are over-sized and super-sized while companies down-size and the resources to fuel it all dwindle to zero. We sell materialism at the expense of what we really value.

Only the most rosy-eyed (or blind) pragmatist would claim such an economy merits a do-not-touch seal of approval.

On principle, the verdict is the same: mixed. Notably, this directly relates to our mixed results. The principles of our free market economy are sound. This explains the positive results above. However, we have applied them neither fully nor well. Therein lies the cause of its shortcomings.

We can see this by examining the standards for grading the market set by economics itself. Economists list several factors required for free markets to work effectively. Among them are:- perfect competition;

- perfect information (for both buyers & sellers); and

- perfectly rational consumers.

We'll discuss the first and last later since we haven't introduced them, but perfect information more than makes the case now.

To work ideally, free markets require everyone to have perfect information in order to make optimal economic choices. Business requires it to determine which goods & services to sell. Consumers need it to know which is the best buy.

Currently, such information mainly focuses on immediate value. Producers total the cost values of labor & materials, etc., and weigh that against reported sales in deciding products and price. Consumers, in turn, weigh these product and price options against their immediate and obvious wants & needs.

Defenders of our current economy might argue that that constitutes (reasonably) perfect information.

But if a consumer buys a product that 10 years down the road gives him cancer, why did he buy it? Assuming he wouldn't have if he had known the health impact, the answer is obvious: imperfect information.

The consumer lacked complete information, and so made a poor economic choice.

This isn't to say that consumers will or won't buy any product with known health risks. Maybe the benefit outweighs the risk. Maybe the risk doesn't bother them. The point though, is this: consumers must have all information to best make that choice.

If we had all information, would we buy products that shorten lives, decay social values, deplete resources, and pollute vs. ones that promote longevity, strengthen society, and are environmentally green?

Again, it's not important whether you answer yes or no. What's important is that you have the information to make those choices. Our current economy does not include this information.

Some might suggest that it's the role of the media and consumer groups to inform us of such things. That's a cop-out. It relies on outside actors to provide something fundamental to economic functioning.

It also sets up conflict. We can see how by rephrasing the above question: How many times do we buy something that we know is less healthy or environmentally sound because it's cheaper than the better one?

That our current economy encourages us to buy products of inferior value is a sign that it's broken. That's not the way a free market should work.

Plus, we can't reasonably expect consumers to know and weigh all values relating to all products in the market. Therefore, if our complex economy is to reasonably convey product information, we need a better way.

Fortunately, there is one. It is not only an exacting information system, but also one fundamental to economics: accounting.

By accounting for these values in the price of goods & services, they are built in to our economic choices. Market forces work on them naturally.

Accounting adds all information on a product. It then gives us the total, down to the penny, in price. It is as near to perfect information as you can get.

So, by its own standard, our current economy falls short.

That is just one specific principle; there are others that we'll discuss later, as mentioned above. But what about broader economic principles? What about economics as a whole? What is it for, 'in principle'?

Economics is a social science. Like other social sciences β geography, history, sociology, psychology, political science, and more β we study economics to understand and improve our lives. Every science exists as a discipline to improve our lives. That is its practical aim. Without that, science is of little or no practical use.

Economics aims to better life by providing the wants and needs of society. We must attempt to address any way in which it fails to do so. Likewise, we must apply economic measures that clearly promise to improve life. This advances the science.

Science is never static; it is ever evolving. Social sciences in particular grow and change as society changes. Our current economic model suited society in the days of abundant resources and limited human impact. Today though, we live in an interconnected global community where every economic decision intimately affects everything else. Resources are less; our imprint is more.

Society has evolved. Economics must evolve with it.

The dollar impact of health, social, educational, and environmental values on our national and global economy is very real. That in itself is reason enough to address them. But even in principle, we must account for these values if we are to be true to our free market ideal.

The free market ideal says that individual buyers & sellers, acting in their self-interest, serve the interest of society.

The vast majority of us would count among those quality health & education, social welfare, habitable urban spaces, clean & sustainable environment, and peace. Yet our economic output fails to meet them effectively. It behooves us to inquire then, what we can do to improve it.

Some might say that public health, education, and environment are not the responsibility of economics. It is true that every field has its own study to guide it. But economics is responsible for those ways in which it impacts other fields.

When profit incentive drives the types of treatments & cures, their distribution, and the availability of medical resources & services, economy plays a direct role in public health. When market forces build our schools (or not), determine teacher qualifications, and produce our textbooks, economy directly impacts our quality of education. When factories pollute our planet and deplete our resources, and discarded goods fill our dumps, economics impacts environment.

If our market economy negatively impacts society in these areas, it is either irresponsible or ignorant to say that it isn't somehow broken.

Still others might suggest that economics is concerned with 'what is', not 'what should be'. These are, in fact, two distinct fields of economics, 'positive' and 'normative', respectively.

Positive economics might simply say that the economy creates problems in these areas. Normative economics would say that economy ought to create solutions, not problems.

But we cannot simply brush off these problems as normative ones. As we've seen, they are very positive. They have real dollar costs. It is not that economy ought not create problems, it's that it is inefficient, according to positive economics, when it does. In real dollars, our economy fails to produce real value. That is as positive as positive economics gets.

In this context, it is somewhat ironic that the adage in question here uses the word 'broke'. Not only is our current economy partly broken in the normative sense, but also it tends toward broke in the positive sense.

By Its Own Admission Economics is well aware of these broad impacts for which we don't currently account. In fact, economics specifically studies them. It just doesn't do much about them.

Economics calls these broad impacts 'externalities', because they fall outside the scope of the immediate transaction.

Economics mainly determines price by immediate and obvious value. For the seller, that is the cost of labor & materials, etc. For the buyer, it is immediate need & desire. Neither buyer nor seller thinks much about environmental impact, long-term health cost, or broad social impact. Those values therefore don't figure into the item price. They are 'external' to the transaction.

It is revealing to note that Adam Smith didn't claim that all self-interest benefits society or that self-interest is always good. He merely argued against the common notion that self-interest β basically selfishness β is innately bad. Smith also realized that competing self-interest in the free market keeps individual self-interest in check, for the good of society.

However, there are times when both buyer & seller agree to a transaction in the immediate self-interest of each, that doesn't serve their long-term interests. For example, cigarettes, which impact the buyer's future health. Or over-forested lumber that dries up the seller's supply, putting him out of business down the road.

Externalities may have positive impact too. Healthy food does more than meet hunger need; it also reduces long-term healthcare. Sustainable forestry does more than build today's home; it ensures housing for every generation. That has enormous, unaccounted for value.

Or the transaction may impact the broad society. How well we educate and train our youth (through education-related transactions, such as school funding, teacher pay, textbook purchase, etc.) impacts crime and poverty, and other social welfare values. It also impacts economic productivity and the wealth of the nation.

Below are just a few examples of externalities that have very real economic costs (negative externalities) or cost benefits (positive externalities).

Negative Externalities:Health -

- Tobacco & alcohol-related conditions;

- Dietary-related illness from trans fats, processed foods, etc.;

- Sickness & disease from pesticides & herbicides;

- Antibiotic-resistant bacteria from medical treatment and animal farming practices;

- Toxic product poisoning (lead paint, household chemicals);

- Pollution-related illness;

Social Welfare -

- Lost productivity due to tobacco, alcohol, and dietary-related illness;

- Alcohol-related traffic accidents;

- Traffic congestion due to overcrowded urban spaces;

- Media and/or entertainment-inspired violence;

- Crime due to overcrowding & urban decay;

- Gun-related violence;

- Cost of war;

Environment - - Global warming from fossil fuel technology;

- Pollution & run-off from industrial farming;

- Loss of resources due to unsustainable harvesting (deforestation, overfishing);

- Land degradation due to mining;

- Manufacturing pollution;

- Waste disposal, including bio-hazardous, toxic, and nuclear.

Economists generally accept climate change as the 'mother' of all externalities, with the greatest cost.

Positive Externalities:Health -

- Preventive value of healthy diet, including organics;

- Preventive value of dietary & herbal supplements;

- Preventive value of lifestyle habits β fitness, meditation, etc.;

- Preventive treatments & medicine β massage, acupuncture, ayurveda, etc.;

Social Welfare -

- Increased productivity due to education & job training;

- Social value of stay-at-home parenting;

- Cultural value of arts & entertainment;

- Social & cultural value of religious & spiritual practice;

- Social value of mentoring, tutoring, and outreach programs;

- Cultural value of youth & other social groups;

- Inspirational value of books, media, and entertainment;

- Economic value of law & order;

- Counseling programs for various ills;

- Economic value of peace;

Environment - - Renewable, clean, and/or alternative energy technology;

- Pollution prevention & control practices;

- Energy conservation practices;

- Green building & other materials;

- Sustainable resource management;

- Sustainable farming practices;

- Planting of trees & other greenery;

- Habitat restoration;

- Biodegradable product use;

- Recycling & efficient waste disposal;

- Conversion of waste to fuel & other uses.

Some of the above externalities are clear and costly, while others are less so. They are not meant as definitive costs to account for. Rather, they give an idea of the many values to consider. The dollar amounts are often significant.

The very existence and study of externalities by economics amounts to self-admission that our current system has flaws. And the scale and range of externalities shows the magnitude of the problem.

Why do we not account for externalities? One reason is that they seem abstract. What is the monetary value of health, social welfare, clean environment, and peace? Yet the costs of these are very real. Healthcare, crime, substance abuse, environmental cleanup, lost productivity, and war all take exacting tolls on our economy. Reams of research studies show real dollar costs for these things. And they are not trivial.

Another reason is that the values are often separated from related transactions in time. The cost of war and re-building, while very concrete, may come long after the making and selling of bombs. The same is true for environmental clean-up of toxic products. Still, regardless of how far removed such values are, their presence cannot be denied. And their cost is real. If you buy a hundred year bond, or a house with a 30-year mortgage, no one says, "That was so long ago, forget about the money."

More to the point, modern research is sophisticated enough to assign dollar figures to such values. Plentiful studies identify the direct and indirect costs of crime, disease, pollution, war, and more. We know major causes and contributing factors to these. We also know costs of corresponding solutions, including education and job training, health care, urban renewal, and environmental fixes. We even apportion costs among the population to identify annual per capita rates. Computer models can today identify the health care cost per pack of cigarettes for an individual smoker, based on their likelihood of developing cancer and other conditions, depending on number of packs smoked per day. We continually refine this study, and given attention, we can achieve far more detailed and precise results.

We don't just know costs; we know cost benefits. We know the cost savings of health regimens like diet, exercise, meditation, preventive care. We know how much pollution is saved by alternative fuels. We have good estimates of the savings of sustainable resource management.

In short, the dollar value of human values is remarkably clear today. It is certainly clear enough to begin to account for them, even if not exact. And it is clearly more accurate than not accounting for them at all.

From a strict economic perspective, our current system amounts to deceptive accounting practice. Failing to account for real costs and cost-savings in daily economic exchange distorts price & profit. Some goods and services then sell below true market value, and others above. Still others never make it to market due to lost profitability. This has disastrous consequences for a free market economy, not in terms of statistics, but in terms of output quality. Quantity may be high, but quality β what we as society value β is low. We create Dollarland.

Economics says that goods with negative externalities are over-produced relative to their true market value; goods with positive externalities are under-produced. In simple language, that means we have more junk products, and fewer good ones.

Value economics removes these market distortions by accounting for the costs & cost-benefits of externalities up front. This creates true market pricing and true profit incentive. This in turn shifts production and demand for goods in the direction of true value.

Economists would say this changes the aggregate 'Production Possibility Frontier', the range of goods & services that society can produce with available resources. The rest of us would simply say we produce better products and thereby build a better society.

What's Broke, What's Not Let's be clear that our economy is not broken in the true sense. Its foundation on the free market ideal is strong, stable, and permanent. What is off is how we apply that ideal. We don't do full accounting. That is why our public health, social welfare, and environment have problems we've not accounted for. In that sense β and that sense alone β our current economy is broken.

Ultimately, we must move beyond the paradigm of broken & fixed all together, because economics is innately an inexact science. While that may seem to discourage so-called fixes, it instead does the opposite. Because economics is innately inexact, it behooves us to improve it as best we can. The many fiscal and monetary policies of today have that very aim.

Economy's fuzziness means that we can't accept failings on the excuse that it's an 'exact' science. If it were physics and the universe was failing, we would have to accept our fate because it's based on immutable laws of nature, hard science. There'd be nothing we could (or should) do about it. But because economics is not absolute, there is no case for leaving an inefficient system as is.

Fortunately, we don't have to change the system. We need only make it work as designed. Value Economics doesn't so much fix the economy as it does give it a good cleaning, overhaul, and tune-up. Then, like a sputtering car fresh from the garage, our economy will 'run like new'.

Our economy has achieved great things; it has also made quite a mess. Ironically, we clean up this mess the same way we created it: with economic solutions. Economy can be the solution, not the problem, if we only give it a chance.

How?

To paraphrase a line from the movie Field of Dreams, make it profitable and solutions will come. Its corollary also holds: make problems unprofitable and they will go away.

That is the promise of Value Economics.

The Fix Externality costs are real and must be accounted for for our free market to work as it should. Value Economics aims to account for these externalities. By making all value internal to the equation, we determine the true market price and create true profit incentive. That brings the best products to market.

The beauty of Value Economics is that it addresses externalities at the time of transaction β as the free market should β rather than after the fact, through remedies. Thus, Value Economics eliminates the need for remedies by eliminating problems at their source.

We don't create health, social, and environmental ills, so we needn't remedy them. Instead, free market incentive drives real product solutions. At the very least, in cases where innovative goods and services are still in development, we pay the cost of externalities up front, so we're not blind-sided down the road.

Value Economics brings external values to our attention at point-of-purchase, to be considered along with immediate value. We then make the best overall economic choice.

The mechanism by which Value Economics does this exactly suits our free market system.

Value Economics informs us of true value at the time of purchase in a direct, yet unspoken way: through price. Rather than moralizing about what we should or shouldn't buy (or worse, legislating it), Value Economics simply totals up the costs & cost benefits β ALL of them β and lets buyer & seller decide in the free market. Everyone is free to act in their self-interest, but the full impact of that self-interest is accounted for.

The wisdom of this approach reveals itself when we compare Value Economics with the way we currently deal with externalities. To introduce this, let's return to Dollarland.

A Tale of Two Economies

~ Part II ~ If you thought Dollarland had problems before, it's got double trouble now.

After several fatal cycles of economic 'growth', two government leaders return from overseas diplomacy and discover the two latest market players plying their trades. The feds represent Dollarland's two political parties, conservative and liberal.

Seeing the goods being sold and pile of bodies, they each campaign to clean up the country. (Naturally, they must campaign before they actually do anything. Never mind that the problem grows worse.) They each craft their government response.

The liberal wants to nationalize the economy and take over business. The conservative vows to 'stay out of the market' and let it resolve itself.

Our two wheeler-dealers like the conservative platform and elect him to office. The bodies pile up and society decays further. By the next election cycle, even the dealers fear the hands-off approach, and so elect the liberal. After a long maze of bureaucracy, government swoops in and our liberal owns the business. There's just one problem; it's not his job to run business and he doesn't know how. He ends gun & drug running but can't produce anything in its place. Dollarland's economy goes into a tailspin.

The next election cycle, the two politicos draw from different elements of their party platforms. The right-wing hard-liner clamors to throw the latest two bums in jail while the bleeding-heart liberal pleads for rehabilitation and social programs to help the disadvantaged men.

Our miscreants like the liberal approach. By the end of his term, Dollarland has two lazy citizens, fat on welfare, contributing nothing to the economy. At this point, even they doubt the value of hand-outs and think they need some discipline. So they next elect the conservative, and agree to jail. Their incarceration costs the nation $50,000 each, per year. Meanwhile, they produce nothing for the economy. At the end of their jail time, the two emerge angry, bitter, and jaded. They return to their old ways fueled with new vengeance.

The lawmakers wise up β just a bit β and try a fiscal approach. The right pledges to deregulate and slash taxes to stimulate the economy. The left promises to tax, regulate, and rein in big business. The dealers prefer the conservative stimulus and elect the 'pro-business' right. But this only emboldens the two and ravages the environment. Drugs grow on public land and toxic weaponry waste fills the streams. Facing compromised resources, the ex-cons elect the liberal in the next election. Gun & drug laws pass, miring business in bureaucracy. Taxes cut into profits. Renegade business is cut back, but production plummets. The output figures aren't pretty.

Our politicians are at their wits end and the nation is in crisis.

Just then, the Dollarland economist paddles ashore in a small rowboat, returning after consulting for others abroad. His dinky boat belies the low status of Dollarland economists.

Having exhausted all other options, the politicos seek out their economic advisor. They brief him. "Dollarland is facing a social crisis: crime, drug abuse, and gun ownership," laments the leftist. "Loss of production, loss of wealth, and a welfare state," retorts the rightist. "Greedy profit-taking and environmental decay," launches the liberal. "Stifling taxes and endless red-tape," counters the conservative.

"We demand to know why!!!" they bellow in unison.

The economist calmly looks at the drug dealer, then the gun dealer, then back at the politicians. He replies in an even tone:

"It's the economy, stupid."

So they tell the economic advisor to do whatever he sees fit.

First he strikes all heavy-handed laws from the books. He removes all manipulative economic regulations. He cancels all welfare programs and hand-outs. He drops taxes. He guarantees private ownership and restores a true free market. Then he approaches DollarlandΓ’β¬β’s two dealer outlaws and asks them what they want.

"Drugs and guns," the scoundrels laugh, scornfully.

"Fine, you can have that," the economist replies, "It's a free country. What else do you want?"

The two eye each other suspiciously. Each pulls the economist aside and whispers, "He wants to kill me."

The economist addresses them, "So you both want to live." They shrug, and nod. Then the economist asks, "How much is your life worth to you?" Neither has an answer, so the economist offers, "Well, your predecessors doubled their net worth annually, until government stepped in. You're down to $25,000 each now, but I got government out, so you should start growing again. Even at a modest 5-10% annually, you're each worth a cool $1 million in about 20 years. Why don't we leave it at that?" The two grudgingly nod, not sure whether to trust the owner of the dinky dinghy.

The economist continues, "Tell you what. As Chief Economist, I also run the Central Bank. I'm willing to invest $1 million in each of you, to use as you please, provided you don't kill your buddy. So long as the other guy doesn't die by your hand, the million's yours to keep."

Now he has their interest.

"What's the catch?" demands the drug dealer.

"No catch," mellows the money man.

"What's in it for you?" asks the gunner suspiciously, hand on his weapon.

"You pay me back 5% of $1 million over 25 years. That's $50,000 per year. After 20 years, I get my $1 million back, and the last five years are profit."

"And we each get the million now?" the drug dealer probes, sniffing out any trick.

"Yep."

They eye each other up & down, then the economist. Then they wince at the rotting corpses of their predecessors all around them.

"We'll do it," they blurt.

"Then it's a deal," agrees the economist. He starts for the bank, then turns. "....By the way, anything else you want?"

"A decent meal would be nice," begs the gun trader.

The economist looks to the drug dealer. "Can you do that?"

"Well, I do have crop experience," he snorts, "and I've been known to whip up some grub." He turns to his former partner in crime. "I'll supply the food if you put a roof over our heads."

Not to be outdone, the gun maker boasts, "That's nothin' compared to crafting fine firearms. You got a deal."

"Great," says the economist. "Why don't you pay him $10,000 for a year's supply of food, and he'll pay $10,000 for the shelter.

They all get busy, and after a few months, the economist returns. There are crops in the field and smoke rising from the chimneys of two mud huts. The gunner-turned-homebuilder is honing his brick making skills out front.

"Nice work," admires the economist. "Tell you what. Now that you've got some disposable income, why don't you take $100,000, buy some construction materials from that overseas tanker that just came to port, and build yourself a nice home?"

"Hmmm...a swanky bachelor pad might suit me just fine," he fancies.

The druggie-turned-farmer comes in from the field with a haul of herbs. Overhearing, he adds, "Hey, I'll buy a load too and pay you $100 grand to build me a pad of my own."

"You're on," the builder shoots back, without his gun.

"What's that you got there?" the economist asks the planter.

"I've been studying up on the medicinal power of herbs. Been growing 'em next to my crops."

The builder perks up. "You got something for my aching back? This construction work's killing me. And my ulcer's been acting up since our fightin' days. And my feet...."

"Why don't you give him a lifetime of healthcare for $100 grand?" suggests the economist to the budding herbalist.

Just then, the two feds arrive, hoping to score political points for all the positive change in the land. Overhearing, they want in on the action. "I can use a new house too," the liberal lays in.

"I've got gout," grumbles the conservative. Then an idea strikes him. "Hey, our foreign trade partner's in the market for grain and tea. Sure would help our trade balance."

"Any market for pre-fab housing units?" asks the builder?

"Hmm...a big storm just knocked out a hundred units south of the border. I'll look into it. You can do some good," lauds the liberal.

So they all do their business and a year later the homes are ready. They move in.

"Hey, not bad," the now certified health provider praises. "I like the fireplace."

"Check out the sky-lit loft," his new builder neighbor brags.

They sink into a couple of lounges on the deck and sip some drinks. "You know...I could get used to this," the herbalist gushes.

"Think I'll get married and settle down," dreams the homebuilder. "I hear two single women just got back from overseas."

"Guess I better plant more crops if we've got families to feed," his buddy replies, putting his farmer hat back on.

"Yeah, and I ought to start on a school and church," the expanding builder adds.

The economist arrives and finds them on the deck. "Wow, nice digs, guys. You wear your wealth well."

"Hey, come up here and join us for a drink, you old money dog!" barks the proud homebuilder.

"Sure," he replies, economically. "By the way, what do you fine gents want me to do with all these guns and drugs?"

They look at each other.

"Burn them," comes the tandem reply, "They bring down the property value."

While clearly fanciful like the first part, this epilogue shows the power of economy to better society simply by accounting for external values. These values represent what we want, and therefore have real monetary value. By awarding value to what we want, economic output creates it.

Attaching profit to human values generates incentive to produce them. This profit-incentive inspires investment, the free-market catalyst for change. In this way, Value Economics uses profit motive to improve health, social welfare, and the environment.

Given the opportunity β and economic incentive β most people will make positive economic choices. Certainly, society as a whole will. And they will pull the rest of society along with them. Value Economics inspires an innovative mind-set in society. Because profit is maximum for products of genuine value, every business seeks to produce them. First, a few bright innovators develop new solutions, then others follow, building on that success. This snowball effect completely transforms society.

Free Market Value

Trumps Market Manipulation Dollarland's initial response is exactly like our current one: bring in government. Because the economy isn't serving the full & best interest of society, we must bring in that bureaucratic servant of the public interest, government.

This clearly shows that government intervention is more a necessary evil than a real solution. We allow government in because that is better than crime, pollution, and public health crises. But it strongly suggests that if there is a better way, we surely should do it.

Government can never and will never solve the problems of externalities. There are several reasons why:- it is an outside remedy rather than inside solution;

- it is a temporary band-aid rather than permanent cure;

- it acts after the fact rather than preventively;

- it manipulates rather than trusts in the market;

- it is bureaucratic, facing an efficient market;

- it relies on unpopular & insufficient funding (taxes);

- it (typically) penalizes negative externalities without rewarding positive ones, slowing growth rather than speeding progress;

- it combats the economy, depleting resources on both sides in an invariably losing battle.

As powerful as government is, it pales in comparison to the broad economy β in every way β as an agent for change in social welfare. No matter how vigorously government pursues objectives, if economic forces work against it, the plan fails.

Government has different strategies for dealing with externalities, depending on whether they are positive or negative. All are flawed.

Legislators address negative externalities mainly through regulation and taxation. Government imposes legal limits to curtail negative impact, and may fine or tax business to further contain the problem. The main flaw here is that this cuts production while providing no incentive for solutions.

Our current economy, which rewards only immediate value, does not do enough to motivate real economic solutions. Two examples show why this is so. In the case of social welfare, business is not rewarded for the positive impact its services might provide. Thus job training, youth groups, counseling services, etc., all of which have positive social value, are under-provided because there is now little profit in it. A different factor slows innovation in fields like medical and energy technology. Here, research & development costs for new solutions can be enormous, discouraging business from pursuing them due to unsure reward.

The government approach does nothing to remedy this. It only penalizes negative impact. That merely curbs production. Positive incentive is needed to shift production to innovative solutions.

Beyond this, government monitoring and enforcement tends to be costly and bureaucratic. It is not the most economically efficient approach.

As a last resort, government calls for 'corporate responsibility' to encourage the best products and business practices. It asks companies to invest in green technology while giving little incentive to do so. Likewise, government encourages consumer responsibility. It urges citizens to follow agency guidelines for healthy diet as a way to contain health costs. It encourages purchase of green products, even though they may cost more.

This method hardly merits response. While the calls are laudable and make good political sound bites, they are wholly ineffective in bringing about substantive change. The best of intentions fail in the face of economic forces arrayed against them.

To address positive externalities, government uses different tools. These are typically tax breaks, grants, subsidies, entitlements, and provisions. Unfortunately, they are all flawed too.

Tax breaks merely amount to giving back what government first took. That in itself is inefficient. Beyond that though, tax breaks are seldom equal to the real dollar value of the positive impact. They therefore do not provide enough incentive for the act. There is a reason tax solutions are rarely enough. Since we always seek to lower them, tax funds are always lacking.

Grants, subsidies, entitlements, and provisions suffer the same shortage problem, since they are funded by taxes. They are also not awarded strictly on economic merit, and therefore may not even have positive impact.

For example, farm subsidies for not growing crops, or for growing certain crops and not others, are questionable economically. Experience with welfare entitlements shows that these often do little, if anything, to improve actual welfare. Government giveaways always run the risk of encouraging idleness. In economic terms, that means zero production.

The last area is government provision. This is where government provides a good or service that the economy doesn't provide itself. Two good examples of this are education and roads. As mentioned, these are chronically underfunded because we do so with taxes. More than that though, provisions are especially underfunded relative to their value. They are called 'provisions' because of their clear need (as opposed to more charitable 'entitlements'). Thus, the quality of these provisions isn't nearly what it should be. This is especially true with education, as we'll see later.

Ironically, the one exception to this is defense spending. This government provision never seems to lack funding. On the one hand it is understandable, since defense is a fundamental need. But any realistic economic view of the matter shows that the real dollar value of peace so vastly outweighs that of mere defense, that large military spending represents a gross mismanagement of society's wealth.

This is why defense spending has such a poor record of maintaining peace. Government monetizes all of the costs of war, but accounts not a penny for the value of peace.

What's more, a cold hard look reveals that negative externalities resulting from our current economy β namely depleted natural resources, but also violent social tendencies β greatly contribute to making the world such a combative and dangerous place.

This points to another problem with the governmental approach: it is fragmented & narrow, rather than comprehensive & holistic.

Besides government, our current economy relies on other inefficient, insufficient, and/or costly ways to address externalities.

The main alternative for negative externalities is the tort system. In court, parties harmed by economic activities can sue those responsible for. Common examples are product safety lawsuits and the well known class action suits against tobacco companies.

This approach has many shortcomings:- only compensates for the problem; doesn't prevent it;

- does little to curtail negative economic activity;

- exhausting & time-consuming legal battles;

- rewards address damage only to plaintiff(s) and may not account for total economic impact;

- expensive legal fees soak up much of the reward;

- often addresses only isolated incidents (e.g. medical malpractice), rather than systemic problems;

- only addresses a small percentage of all negative externalities.

For positive externalities, two of the main non-government handlers are charity and philanthropy. These, while highly laudable, have their own shortcomings. Like government, they typically lack the funds to satisfy the economic need. Also, fund dispersal is determined by charitable boards, often with specific missions, rather than optimal economic need.

Perhaps worst of all, this system reduces the businesses & organizations that have this positive impact, particularly social & environmental groups, to being beggars & welfare recipients. Because our economy doesn't reward them for the real dollar value they create, they cannot profit, and therefore must instead rely on charity funding.

But there is a more important economic impact. Because these groups cannot profit, there is no economic incentive for them to exist! Clearly, that is no way to encourage such valuable groups.